2021.3.5

Lessons from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake: IRIDeS researchers talk about recovery and passing on disaster memories to future generations (1)

Book title: 51 Approaches to Disaster

Science: Lessons from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake

Editor: IRIDeS, Tohoku University

Publisher: Tohoku University Press, Sendai

Price: 3,000 yen + tax

ISBN: 978-4-86163-357-7 C3000

IRIDeS compiled a book titled 51 Approaches to Disaster Science: Lessons from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, which was released in March 2021— the 10th anniversary of the Great East Japan Earthquake. In this book, IRIDeS researchers, as well as several other scholars from collaborating organizations, summarized the problems that were revealed by the 2011 disaster, the progress that has been made to date, and the remaining challenges—all from respective fields of expertise. This book is written in Japanese and consists of 51 chapters (one topic per chapter) and four columns under four major themes: "disaster assessment and prevention,” “humanity and society,” “health,” and “domestic and international cooperation."

On January 25, 2021, four of the book chapter authors gathered for an online discussion to talk about recovery and how to pass down disaster lessons for future generations. Deputy Director Prof. Hiroaki Maruya, (specialization in economics) was the moderator; Associate Professors Shosuke Sato (disaster informatics), Daisuke Sato (history) and Elizabeth Maly (architecture) also participated.

Deputy Director Hiroaki Maruya

Deputy Director Maruya (hereafter Maruya): Today, I would like to ask each of you to introduce the chapter you have written and then we can all discuss it together. We will begin with you, Dr. Shosuke Sato. Please start.

Associate Professor Shosuke Sato (hereafter S Sato): I wrote Chapter 32, “The Science of Passing on Memories.” The Sanriku region has repeatedly dealt with tsunami disasters in the past and has tried to pass on their lessons and experiences in various ways. However, even where similar tsunami monuments had been built, there were differences seen in the extent of damage from the Great East Japan Earthquake. For example, both Omoe Aneyoshi, Miyako City and Nakazawahama, Hirotamachi, Rikuzenntakata City, Iwate Prefecture, have a tsunami monument that reads “Don’t build a house below here.” However in 2011, the damage of the former district was small, whereas the latter district suffered many victims.

Dr. Shosuke Sato

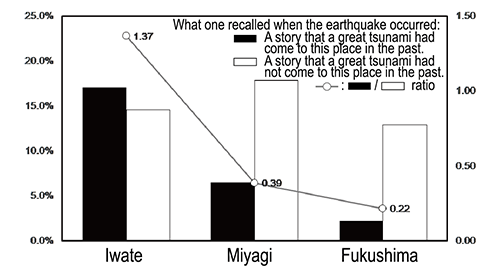

I then hypothesized that the extent of the damage could be associated with knowledge about past disasters; and so I proceeded to conduct a study. When comparing Iwate and Miyagi Prefectures, mortality rates tended to be higher in Miyagi Prefecture. In Iwate Prefecture, a large percentage of people recalled a past tsunami when the earthquake occurred. In both Miyagi and Fukushima Prefectures, there was a rather common belief that “Tsunamis do not come to this place.”

It is an obviously important matter to pass on the fact that a disaster occurred in the place to future generations. However, I found that, while some areas successfully passed on disaster experiences, others could not; furthermore, while some areas mitigated the tsunami damage with the lessons that have been passed down, others could not.

I have also explored the characteristics and effects of passing down disaster memories quantitatively. Our study found that a disaster is most likely to be remembered when it is told by a person who has personally experienced it; additionally, it is also - to some extent - effective when these memories are just simply conveyed by a human—even if the person in question did not actually experience the disaster first-hand. Lastly, I am assisting in training and informing the young generation who will help pass on these important stories of disaster to future residents.

Figure: Recalling past tsunamis at the time of the earthquake occurrence

(Source: Assoc. Prof. Shosuke Sato)

Associate Professor Daisuke Sato (hereafter D Sato): If only one person out of 100 has knowledge and awareness of past disasters, precious lives could be saved—perhaps the entire community does not have to have the knowledge. How these memories are communicated should also be focused on. I consider that a quantitative approach, as well as a qualitative approach should be important in this endeavor.

My specialty covers the Edo period. In this period, people did not have the freedom to move from one place to another. Thus, it was more than likely easier to pass on disaster memories within a community. In modern times, however, it has become far more difficult to pass on personal disaster experiences due to the mobility of the population, as well as the decline of communities in general. Preservation of the “3.11” legacy will be a task of the upmost importance.

S Sato: In the future, I would like to study how the existence of key people and how methods of communication are associated with passing on disaster memories and with actual evacuation behavior. There were cases in the past where passing on disaster experiences was disrupted because of a relocation of the community to higher ground. I would like to carefully consider this while passing on stories and memories of the Great East Japan Earthquake.

Associate Professor Elizabeth Maly (hereafter Maly): It is also becoming important to pass on how disaster areas have been reconstructed, not just stories of the disaster itself. It is necessary to integrate regional reconstruction and disaster storytelling, helping local people to easily share their experiences with people from outside of their communities at a facility that is built to pass on their disaster memories to a broader audience. What do you think about passing on memories of the tsunami risk and evacuation that immediately follows after a disaster; what about the long-term perspective for the future?

S Sato: Facilities for the purposes to convey the disaster began to appear about five years after the 2011 disaster. Related to your question, early facilities tended to focus on earthquakes, tsunamis, and emergency response; while more recently built facilities tend to have more content that is related to reconstruction. How to update the existing content of the initially created facilities will be important in the future. Also, there is an example of the disaster area of the 2004 Chuetsu earthquake, that successfully became a tourist attraction that pulled in many visitors. I hope this will be the case in Tohoku as well.

Maruya: In the past 10 years, we have addressed what information needs to be preserved and how. In the next 10 years, I hope that the younger generation of researchers will develop technology that will allow future generations easy access to the information, especially digital data—including videos. This would not only be found at heritage sites and monuments, but anywhere they need to be. Next, Dr. Daisuke Sato, please start.

For inquiries, please contact IRIDeS PR Office at +81-22-752-2049 or email: @